I was born as a Catholic in Poland, a country where 94% of the population is also Catholic. Some of my earliest and most profound memories are of nightly prayers and weekly masses. I was told that God created the world, that he was always watching us and judging our behavior. He would choose to send us to either heaven or hell for all eternity based on this standard. It seemed like a very big deal. I resolved to practice religion faithfully, so that I could be good and get into heaven.

The church I attended upon moving to the United States had stained glass windows and intricate artwork throughout. I looked up at the face of Thomas Aquinas on the vaulted ceiling, thinking of the men who had painted it. In those moments, I felt especially thankful to God for having given me life. The Biblical stories were a call to ethical behavior, in the form of ancient stories written by wise men. It made me feel important to be there and listen to them.

Unfortunately, feelings of unease often undermined my joy. It made me uncomfortable to constantly refer to myself as a guilty sinner, despite not knowing what I had done wrong. It made me uncomfortable to think of somebody constantly watching me. Most of all, it made me uncomfortable when the priest lambasted greed, quoting Matthew 19:24: “In fact, it’s easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to get into God’s kingdom.”

I respected and admired wealth. I had figured that if I was a good Catholic, I could gain the moral virtue to be successful, and that God would certainly send me to heaven. This was clearly not true, by the Bible’s own standards. At first, my feelings of guilt inspired new fervor. In eighth grade, I would bring a prayer book with me to school and thought about becoming a nun. But I could not repress the sense that religion was incompatible with my individualism and love for science.

After much study and deliberation, I realized that I had fundamental disagreements with Christian doctrine. The Catholic doctrines of serving others and faith without proof, which are essential to the religion, are fundamentally incompatible with my personal beliefs. I liked people but did not want to grovel before them. The more that I learned, the more problems I discovered. No explanation could reconcile scientific findings with many of the Bible’s claims. Learning about religiously-motivated barbarism, such as the Spanish Inquisition, left me aghast. My interest in history opened a new world to me—the world of philosophy. I saw that other, non-religious thinkers had ideas about how to live life with a broader and more integrated scope.

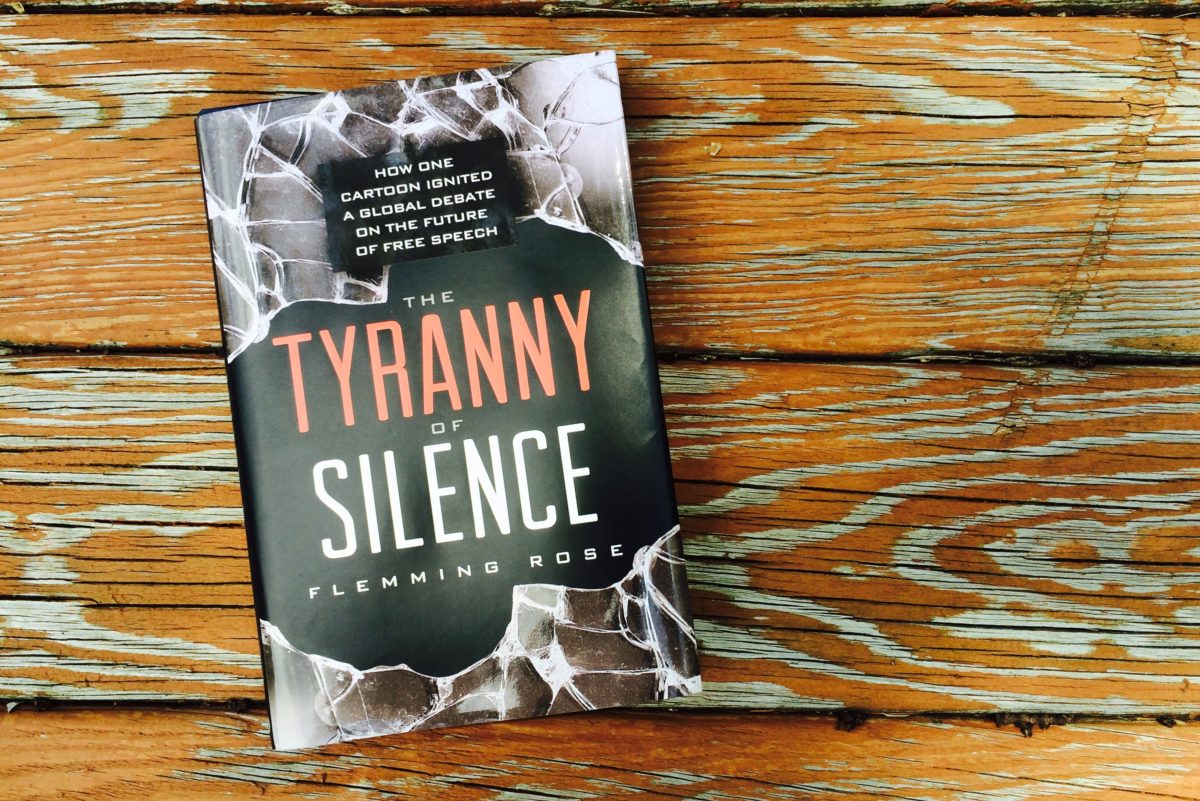

I found Anthem by Ayn Rand in my local library in ninth grade. To my amazement, Rand defended the importance of the individual and his independent mind. Except for the U.S. Constitution’s preamble, this view was radically different from anything I’d heard. Reading more of Rand’s works gave me courage in my conclusions, even if others disagreed with me. My teachers who condemned capitalism weren’t necessarily right, and not going to Church didn’t make me a sinner.

I came to understand that I should not accept contradictions or claims based on faith, in any area of my life. I learned that I should use reason for the purpose of making my life the best that it can be. It is my own life that is my highest value—not the life of anyone else, nor the view that anybody else has of me. A person’s proper place isn’t to grovel before God or before society, but to honor himself, use his mind, and pursue rational values.

Rand eloquently sums up the booby trap that is “original sin” in a famous speech in her novel Atlas Shrugged:

That which is outside the possibility of choice is outside the province of morality. […] To hold man’s nature as his sin is a mockery of nature. To punish him for a crime he committed before he was born is a mockery of justice.

We aren’t born as sinners. Christianity teaches that God dooms us to suffer, and that we become moral by virtue of our suffering. But we aren’t doomed. We have a choice to think or not to think. Humans have free will; we can choose to integrate or to evade truth, we can choose what we care about and what actions we take.

Adopting a rational philosophy enabled me to find happiness and self-esteem. It gave me the conviction to pursue my goal of becoming a software engineer, and to put all my effort into mastering my craft. I learned that there is no arbiter of morality except for reality itself; the effort I put in will determine my success. What is moral is that which furthers my life and the rational goals that I set.

Posts in the Life section are intended to allow our readers to discuss how they understand the principles of Objectivism and apply them in their own lives.