The problem with the perceived divide between work and life.

With graduation day looming for this year’s college class, millions of students will soon be joining those already seeking employment, while the employed nervously hope their positions are safe. Media commentators and political leaders, following the public’s lead, have fixated on the issue of “jobs”–how many there are, how to get one, how to create more.

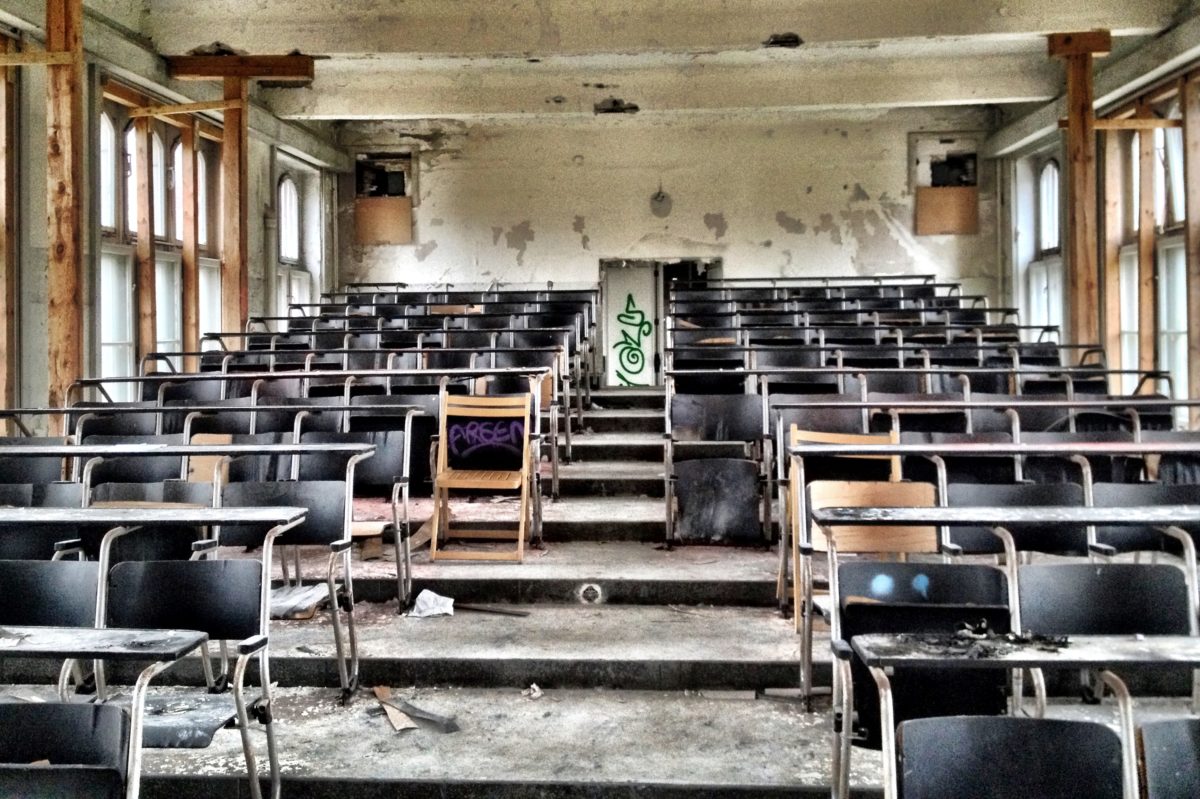

But underneath this preoccupation we find a long-standing feature of our culture: a distaste for work. However fortunate they feel to have a job, how many people still begin their week with the refrain “It’s just another Monday” and end it with “Thank goodness it’s Friday”? How many bookstore shelves are stocked with best-selling strategies to work as little as possible or avoid it altogether? How many employers highlight their ability to offer employees a generous “work/life balance”, implicitly suggesting the two are mutually exclusive? How many college students are told to make the most of their time on campus, a hedge of enjoyment against future drudgery in the working world? Complaining about work is more than popular—it’s expected.

The reason so many people are worried about getting a job is clear: jobs are increasingly scarce. But what then is the reason this anti-work outlook still persists?

As an isolated phenomenon, one can find ready explanations for this outlook. Some people are paying the price for pursuing careers they don’t actually enjoy, careers they chose arbitrarily or to please others. Some don’t pursue careers at all, settling for jobs that permit them to collect a paycheck and nothing more. Still others find themselves in difficult circumstances involving a neurotic boss or insufferable coworkers, and conclude that such is inherent in any job.

But these particular mistakes or misfortunes don’t explain the near-universal negativity towards work. People often encounter frustration finding love or staying in shape, but nevertheless continue to view romance and fitness positively. Why is work different?

The answer lies in a deeper, commonly-held view: that the ideal life is a life of idleness, free of productive effort. On this view, work is like a bitter medicine—an unpleasant but necessary evil. It is the garden-of-Eden attitude, that man led an idyllic existence in the Garden of Eden with everything provided by God, until he committed the original sin and was banished, forced to provide for himself by the “sweat of his brow”. Or, in the secular version of the same outlook, work is foisted upon us by society, to which we surrender our freedom and happiness by mindlessly joining the “rat race”. Regardless of its form, the idea (a reality that forces us to work) and its consequence (resentment) are the same.

But there are also those rare individuals who enjoy—or even love—their jobs. Their numbers include people in all types of professions—the chipper and efficient secretary, the mechanic or handyman that takes pride in his work, and the school teacher who delights in the revelations of students. Are these people born with a blissful ignorance of the nature of their toil? Or have they figured something out that the rest haven’t?

If a man bitterly complained, after imagining a world in which he had four arms, that he is cursed to have only two, we would answer that the complaint is silly, based upon an arbitrary desire. The anti-work mentality is guilty of the same error: it starts with the fantasy of a world without the need for work, and then bemoans the fact that such a world doesn’t exist.

In reality, there is no such thing as a Garden of Eden in which every desire is effortlessly satisfied, and consequently there is no valid basis to resent its absence. Work is inherent in the very nature of life. A living being is one that engages in a constant process of self-sustaining action. Even the most passive plant must turn itself to capture the sun. Animals must hunt and forage. And we, as human beings, must undertake the effort necessary to produce the much larger range of values that sustain a life well-lived, from food and shelter to transportation and entertainment to friendship and love. Indeed, everything we do, from climbing out of bed to seeing a movie requires a certain amount of effort. To view work as an activity separate from life, as if one ends when the other begins, ignores this crucial fact: that work is the basic activity through which we get what we want out of life, both from the wealth it creates, and ideally, from enjoyment of the process. To resent work is to resent that fact—it is to resent life itself.

One might object that the necessity of productive work doesn’t make it enjoyable. But there are many things in life that are necessary. We have to eat, to clothe ourselves, to learn. Along those lines, we’ve created gourmet meals, a fashion industry, and a vast array of educational avenues. In effect, we’ve transformed the necessities of life into some of its most pleasurable aspects. Our attitude toward work should be the same: since I must do it, I will choose to do it in a way that I enjoy. Fortunately, the advent of the modern economy has afforded us the opportunity to be selective about the type of work we do.

That’s not to say one can simply adopt a pro-work perspective and suddenly the perceived drudgery of one’s job will be transformed into bliss. Fulfilling work is itself a value to be achieved. There are many potential barriers to enjoying one’s work. Some parents, for example, pressure their children to pursue careers they deem practical or easy, despite the child’s actual interests. Many of us are taught that we’re victims of unseen disadvantages, a self-defeating view promoting an entitlement mentality that discourages individual independence and ambition. The government increasingly regulates and taxes our jobs and earnings, making a growing portion of our working lives dictated by others and without reward. In all these ways and more, the cards are stacked against the proper enjoyment of productive work.

But they don’t have to be. The first step is to call into question the anti-work premises that have infected our culture, and replace them with views that treat work as a life-serving virtue rather than a pernicious burden. Only by understanding what productive work can and ought to be are we are able to pursue and undertake it in a pleasurable way. To this end, there’s no better place to look than the writings of perhaps the foremost defender of the value of productive work, Ayn Rand:

“Productive work is the road of man’s unlimited achievement and calls upon the highest attributes of his character: his creative ability, his ambitiousness, his self-assertiveness, his refusal to bear uncontested disasters, his dedication to the goal of reshaping the earth in the image of his values.”

If that’s not a reason to look forward to Monday morning, what is?

Noah received his BS in Computer Engineering and MS in Information Assurance from Iowa State University. He currently works in the defense industry as a software engineer in St. Petersburg, Florida.