The Kony 2012 video calls for an end to Joseph Kony’s reign of terror as a warlord in Uganda. It was created by the Invisible Children charity organization and has been shared by many on Facebook, accumulating tens of millions of views on YouTube. Celebrities including Bill Gates, Rihanna and Taylor Swift have endorsed the Stop Kony campaign. Needless to say, the video is one of the most viral films in recent memory.

Joseph Kony has abducted 30,000 children and has forced them to serve in his army, which is responsible for the death, mutilation, and rape of thousands of Ugandans. He represents a war against the basis of civilization: the right of each person to pursue happiness, free from violence. The arrest of Joseph Kony is a cause that everyone can support.

Yet there are many problems throughout the world that we could concern ourselves with, so why is this issue unique among all the other problems facing Africa or the rest of the world? Robert Mugabe killed an estimated 20,000 people in an uprising against his rule in the 1980s. In 2004, Mugabe’s policies caused the death of 10,000 more people, and he still rules Zimbabwe today. A food crisis struck Eastern Africa last summer that jeopardized the lives of 9.5 million people, yet no viral campaign emerged to end that catastrophe. Humanitarian crises and wars like those in Central Africa are found around the world in countries such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Pakistan, Yemen, Syria, Sudan, and Burma. So why do so many people suddenly care about arresting this particular warlord?

The answer is that the Kony 2012 video succeeded in making Joseph Kony “famous”: the popularity of the video made it fashionable for young people to advocate for his arrest. Many share the video on Facebook because their friends have done so, and they care about stopping Kony because others have told them that they should. The video exploits its viewers’ feelings of guilt and pity, by contrasting the opulence of America with the hardship of Ugandan children. People who share the video believe that they have done something to stop a Ugandan warlord, and feel good that they have become a part of a movement to help others less fortunate than themselves.

Many have criticized the Kony 2012 campaign for these reasons. Some say that the campaign exemplifies “slactivism,” the cursory measures people take to feel better about themselves even though they do not create any real change. In this case, people share the Kony 2012 video but then continue on with their lives.

But should one take one’s time and money to help children in Uganda, as suggested by those who criticize Kony 2012 for its “slactivism”? And why should one be criticized for not taking time and money away from one’s life to give to Ugandan strangers, when doing so is presumably impractical?

People think that they should do more to help capture Joseph Kony because they have adopted the “help-others” moral learned from parents, religious leaders and other social authorities. From an early age, we are taught to believe that helping others is our highest priority, while doing things solely for ourselves is wrong. The same feelings of guilt and pity that inspired us to share the Kony 2012 video motivate us to heed the lessons taught to us by others. We are taught to think that those who are well-off need to help those who are less well-off, and many will help others to alleviate the guilt that they would have felt had they not helped them.

Is blindly following a moral outlook handed down to us by authority figures the best way to decide if we should think that we need to help others as our top priority? Accepting what others say without question amounts to a classic argument from authority. As The Undercurrent’s Valery Publius writes:

Nothing justifies this belief in unchosen moral bondage, which has been passed down, largely unchallenged, from our elders and our religious texts. Why should inscrutable authorities like these guide our lives and govern our societies? Should we not instead formulate our moral principles by the same method that produced past revolutions in science and technology, the method of rational demonstration based on observable, natural facts?

Before people criticize those who support Kony 2012 in response to social pressure, they should ask themselves if they adhere to their own moral principles for similar reasons. If they did so, they would realize the need for an ethics grounded in reality. We need to revolutionize our way of thinking and realize that individuals thrive when pursuing their own goals, unencumbered by the guilt imposed upon them by their Facebook peers.

When we learn of criminals like Joseph Kony, we should feel angry and recognize the need to capture them, but we should not think that an unearned guilt compels us to action. Instead, we ought to use our own independent criteria to evaluate how to respond to warlords like Joseph Kony, if at all. Whatever we do, we should do it not from social pressure but because we have decided for ourselves that it worthwhile.

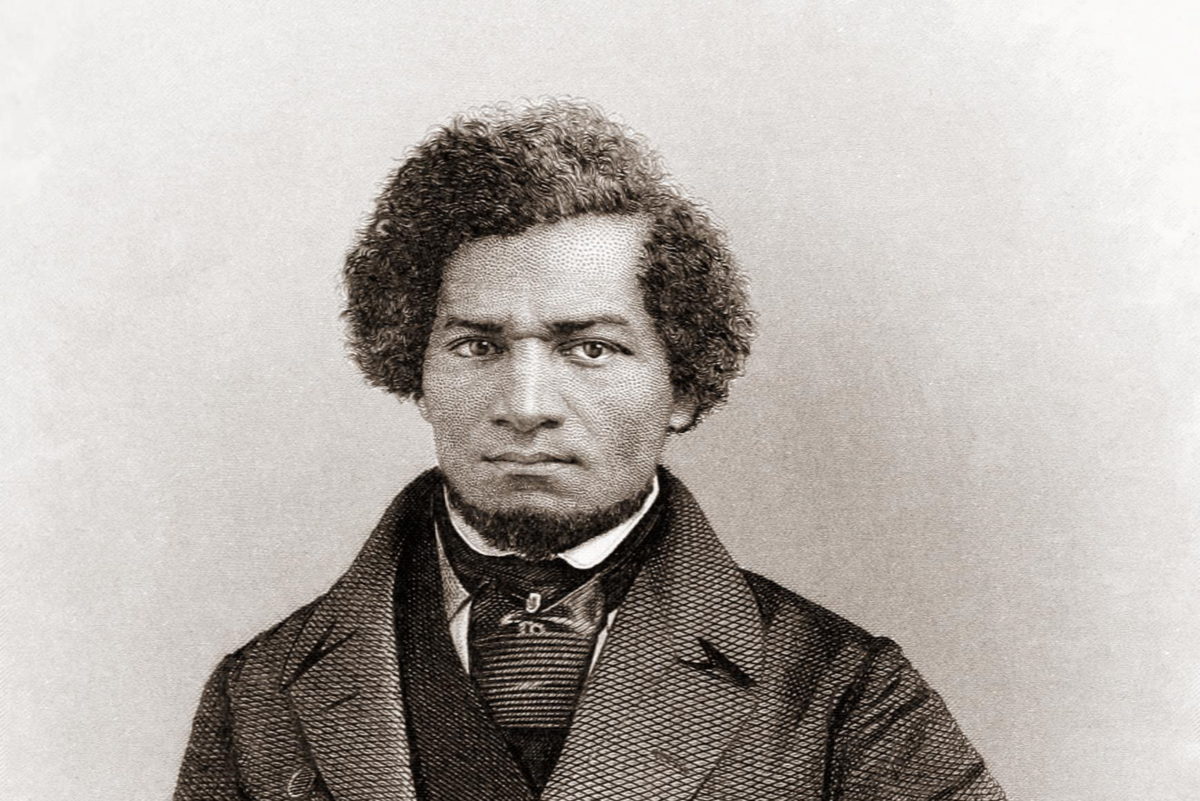

Image courtesy of Flikr user Robert Raines.