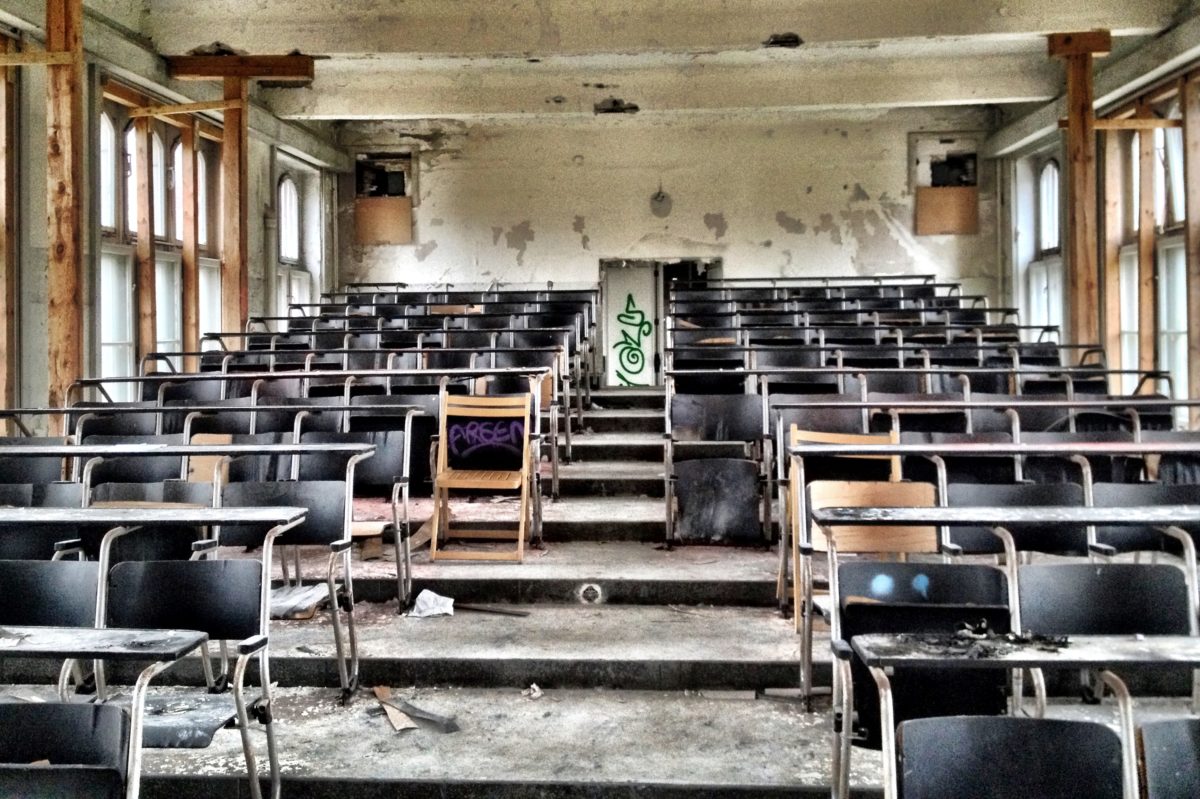

Today’s generation of college students grew up on the notion that if they did well in school and got a college degree, good things were ahead. But recent news darkens this outlook. These days, everyone is facing stiffer competition for employment: in May of 2013, there were 7.2 million people seeking work, up dramatically from 5.5 million in May of 2003. This is an increase of 30%, even as the total population has increased by only 9%. A recent report indicates that unemployment among Millennials aged 25 to 32, of all educational stripes, is higher than that of Generation X and Baby Boomers, among others. As the ratio of jobs to job-seekers has increased, the percentage of college graduates who are unemployed or underemployed has grown as well. The 2013 unemployment rate for those over 25 with at least a bachelor’s degree was around 8%, compared with just 5% in 2003.

Students desperately need these jobs just to cover the cost of their education: since 2003, average student debt has increased from $19,300 to $35,200. Worse still, a 2013 report notes that while there are currently 28.6 million jobs in the economy requiring a college degree, there are currently 41.7 million employed college graduates. This means that about half of recent college graduates are working at jobs that don’t require their degree—up almost 10% from the year 2000. Present conditions simply don’t inspire the college endeavor.

Quality jobs today are thus scarce at a time when students need them the most, giving students a greater incentive to settle for jobs for which they are simply overqualified. In the face of a daunting job market, what can today’s generation of students do differently to make the most out of their decision to go to college?

To begin with, students must face the fact that competition for the best and most promising jobs will be tougher than it was a decade ago. Obviously, success inside the classroom is crucial to success after school. But even if students go to college and perform exceptionally well academically, it’s important not to overlook that university life presents more than just the opportunity to learn academic content and methods. Rather, it presents a unique opportunity for young adults to hone the particular virtues of character that will prepare them to pursue a happy, successful life.

“Character” is the essence of who an individual person is, the enduring set of practical and emotional habits that result from his chosen convictions and values. Character traits, such as ambitiousness and competitiveness, differ from cognitive skills, such as mathematical proficiency and the ability to play the piano, insofar as character traits are the products of life habits—habits that are useful not only in work but in all of our other pursuits. In fact, cognitive skills are often themselves the results of life habits. “Virtues” of character are the particularly pervasive character traits which can empower a person to live his life and live it well.

The job search itself requires virtues that students have the chance to develop further while attending school. The best jobs for graduates don’t come simply packaged with an earned degree. Searching for the right job requires a constant, carefully planned course of action. If students emphasize the development of their character throughout college, they have the opportunity to hone the virtues that are essential not only to finding a good job, but also to their pursuit of happiness more generally.

Productiveness is the most obvious of those virtues. A 2012 study of how college students allocate their time each day shows that the average student spends just 3.4 hours each day on “school related activities,” including class and homework. That hardly seems to be an adequate amount of time to allot to school work each day, and raises the question of whether students today are being as productive with their time as they could be. To be sure, college should be a fun experience—but the constant partying that permeates today’s university atmosphere flies in the face of the notion that celebration presupposes some achievement to celebrate.

The productive student will go beyond merely attending class and performing well. He will both engage himself in the active pursuit of his hobbies through the many avenues on campus, and begin to build a social and professional network through campus clubs, part-time work, or volunteering. This active, productive mindset is critical to the job search: employers desire resumes showing evidence that a job candidate is a self-starter who creates and pursues opportunities for himself—which suggests that he would do the same for them.

Going to college today represents a sort of rite of passage into adulthood from adolescence, in no small part because it is a suitable environment for a young person to develop independence. Most students will leave home for the first time, exiting a world where teachers hold their hands and parents do their laundry, and entering an entirely new social environment, where professors are relatively hands-off and parents are nowhere to be found. But how many students entering college truly endeavor to foster their own independence? How many conceive of their life, and the form it will take, as their own responsibility and no one else’s? As the numbers indicate, not enough: while less than one-third of college graduates 18 to 24 still lived at home in 2001, that figure rose to almost half by 2011.

While many students need their family’s support during college, the gravity of the change from living at home to attending university brings new opportunities for growth. It provides the perfect setting for young adults to learn to do things for themselves, starting at first with simple things like cleaning their dorm rooms and getting assignments in on time. But if students think of university as their own personal experiment where they alone, in a new and exciting environment, have the opportunity to craft themselves into the kind of person they’d like to become, then the kind of independence learned in college will be far more useful than for just doing the laundry or even getting that A.

By doing everything from trying out new and challenging hobbies advertised at the campus club festival, to developing distinctly personal convictions from in-class discussions and conversation with peers, students have the opportunity for a world of independent growth. College can prepare students to develop a new and unique sense of who they are, and to face a market of employers searching for those outstanding few candidates with a confident and developed sense of identity. Employers want confident students who are willing to put themselves out there for the world to see.

College students must also learn to defend the fruits of their independent productiveness with the virtue of integrity. Not only do students need to decide which ideas, values, and career goals are the right ones, they also need to act in accordance with their decisions. The graphic design graduate who settles for a job coaching soccer, the economics graduate who settles for a job as a supervisor at the local supermarket, the physical therapy graduate who settles for a job as a salesperson at his family’s car dealership—none of these graduates had the integrity to say “no” to or to break free from a job they never desired. Values have no value if they aren’t put into practice.

Of course, finding the ideal position may be no small feat when jobs are scarce and opportunities more limited than they were a decade ago. But it’s possible for graduates to retain their integrity—their commitment to their deepest values—even if they’re unable to earn that ideal job at first. Graduates with integrity will relentlessly pursue the job that allows them to translate their values into action, if at first they fail to do so. While the first job right out of school may not be ideal for many, it offers an invaluable opportunity for graduates to meet professionals, apply skills and learn new ones, and with time, springboard from that first job to a better one.

Those graduates who end up unemployed or working less-than-ideal jobs often tend to blame the job market. There’s certainly merit in that sentiment. But that way of thinking won’t change anything or help anybody. Rather, graduates should be asking the same question that current students must ask themselves: have I really done all that I can do? That analysis begins—but does not end—with grades and job performance. It extends to the further question: am I really all that I can be? The answer to that question lies in whether students have used college as an opportunity to become productive, to foster independence, to act with integrity, and to develop other virtues of character. These virtues will guide young persons though college as students, help them to navigate the unsure waters of the job market as graduates, and give them the tools to pursue the best life possible as mature adults.

Creative-commons licensed image from Flickr user Dick Johnson.